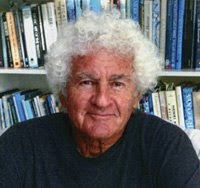

Dr. Arthur Janov was a psychologist and author of 11 books, including the international bestseller, The Primal Scream and Primal Healing, published in November 2006. He was the Founder and Director of the Primal Center in Santa Monica, California.

Dr. Janov received his B.A. and M.S.W. in psychiatric social work from the University of California, Los Angeles and his Ph.D. in psychology from Claremont Graduate School. Before turning to Primal Therapy, he practiced conventional psychotherapy in his native California. He did an internship at the Hacker Psychiatric Clinic in Beverly Hills, worked for the Veterans’ Administration at Brentwood Neuro-psychiatric Hospital and was in private practice for 1952 till 1967. He was also on the staff of the Psychiatric Department at Los Angeles Children’s Hospital where he was involved in developing their psychosomatic unit.

The course of Dr. Janov’s professional life changed in a single day in the mid-1960’s with the discovery of Primal Pain. During a therapy session, he heard (as he describes it), “an eerie scream welling up from the depths of a young man who was lying on the floor”. He came to believe that this scream was the product of some unconscious, intangible wound that the patient was unable to resolve. Since then, Dr. Janov has devoted his professional life to the investigation of that underlying pain and the development of a precise, scientific therapy that could mitigate its lifelong effects.

Dr. Janov had been conducting revolutionary research in the field of psychotherapy for more than three decades. As the originator of Primal Therapy, he has treated thousands of patients and conducted extensive research to support his thesis that both physical and psychic ailments can be linked to early trauma. He has concluded that patients can dramatically reduce such debilitating medical problems as depression, anxiety, insomnia, alcoholism, drug addiction, heart disease and many other serious diseases. In 1970 he introduced his radical new approach to therapy to the general public in his first book, The Primal Scream, which became a best-seller and has since sold more than a million copies worldwide.

In the last 30 years Primal Therapy has established itself as the only therapy producing deep changes in a host of psychosomatic symptoms and psychological problems. As Director and Supervisor of Research with the Primal Foundation Laboratory, Dr. Janov was the first psychologist to submit his results to scientific scrutiny. Studies at Rutgers, the University of Copenhagen, St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in England and the University of California at Los Angeles have all supported his theory that Primal Therapy can produce measurable positive effects on the function of the human brain and body.

Dr. Janov and his wife, Dr. France D. Janov, co-director at the Primal Center, have lectured worldwide on Primal Theory and Primal Therapy, including to the Royal College of Medicine, London, England; Hunter College, New York; Karolinska Medical and Research Center, Stockholm, Sweden. His work has also been the subject of a PBS special in the United States and of documentaries in Germany, England, France and Sweden.

The latest research conducted at Dr. Janov’s Primal Center on the effects of Primal Therapy on the brain was performed by Dr. Erik Hoffman, former Professor of Neurophysiology at Copenhagen University. This research has shown very clear changes in the brain as a result of feeling.

In 1989 in an effort to expand the Primal network, Dr. Janov established Dr. Janov’s Primal Center in Santa Monica, California with his wife, Dr. France Janov.

Arthur Janov passed away at October 1, 2017.

Source: http://www.primaltherapy.com/about-arthur-and-france-janov.php

Bibliography

- The Primal Scream (1970) – (revised 1999)

- The Anatomy of Mental Illness (1971)

- The Primal Revolution: Toward a Real World (1972)

- The Feeling Child (1973)

- Primal Man: The new consciousness (1976)

- Prisoners of Pain (1980)

- Imprints: The Lifelong Effects of the Birth Experience (1984)

- New Primal Scream: Primal Therapy 20 Years on (1992)

- Why You Get Sick and How You Get Well: The Healing Power of Feelings (1996)

- The Biology of Love (2000)

- Grand Delusions—Psychotherapies Without Feeling (2005); unpublished manuscript available at the Primal Center’s website

- Sexualité et subconscient : Perversions et déviances de la libido (2006)

- Primal Healing: Access the Incredible Power of Feelings to Improve Your Health (2006)

- The Janov Solution: Lifting Depression Through Primal Therapy (2007)

- Life Before Birth: The Hidden Script That Rules Our Lives (2011)

From Primal Healing:Case Study: Nathan (page 120 – 122)

I’ve

been on edge lately. Actually, I’ve been losing it really, but with

good reason. Everyone is conspiring against me, even the therapists.

That is how I went into my session on Tuesday. So you think I’m smoking

dope again, and you told all the other therapists and everyone now hates

me. Valerie (my therapist) didn’t respond much, except to say, “How

does that make you feel?” I’m always getting screwed; somebody is always

out to get me. I’m always getting blamed for something, and everyone

always ends up hating me for some reason or another. As I’m saying this,

I start to feel a knot of tension in my stomach and a deep sadness. My

eyes start to get blurry, and it’s hard for me to talk. What’s

happening? Valerie says that I feel that I’m not good enough, I can’t do

enough, and nothing I do will ever be enough! I can’t please everyone. I

can’t be perfect! I start to break down and cry.

The

feeling keeps penetrating and my crying becomes serious. I lose all

sense of time, and then out of the blue, this flashback pops into my

head. I’m in high school during computer class hiding my face in my arms

and pretending to sleep while everyone else is busy doing their work. I

was miserable back then, and I would usually spend my days in class

sleeping or pretending to sleep. The teacher called me up to her desk,

and I was thinking, “Oh shit, I’m in trouble again,” or maybe she was

going to ask me if something’s wrong. That’s what I wanted her to say:

“Is something wrong Nathan? What’s the matter? Can I help you? You can

talk to me, I’ll listen.” But no, she asked me some stupid question

about my homework, I answered and went back to my desk to sleep.

Now

the tears are pouring because nobody can see how much I hurt, nobody

wants to help me, nobody cares, and I feel worthless! My muscles start

to clench and I start to cough. I cough and cough and cough, to the

point where it feels like I’m going to vomit. But I don’t. A pressure

seems to release after these coughing fits and I just lay there limp and

flooded with tears. I calm down a bit and Valerie says, “Ask for help.”

“No, I don’t want to!”

“Ask.”

“No,

I don’t want to; they should have been able to tell. They should have

been able to see how much pain I was in, how hurt I was.”

“Ask.”

“Help

me! Please help me! I need help!” And I’m back in it, full blown

crying, spasms, muscles tensing up, and coughing. It goes on like this

until I remember that phone call I made.

Just

a few days ago, on Mother’s Day, when out of guilt more than anything, I

called my mom. “Happy Mother’s Day,” I said. But all heard back was how

well my brother is doing. He just bought a new motorcycle, he just got a

new dog, he just did this, he just did that. And I feel like shit,

because my life is shit, and I can’t get it together. She just keeps

rubbing it in, making me feel worthless. Nothing I do is good enough. I

can’t do anything right; I’m such a disappointment! Here come the tears

again. I realize that these present-day feelings stem from this. These

memories of being neglected and manipulated all my life. But not only

that, as the session winds down, my therapist tells me that she didn’t

think I was smoking dope, and she didn’t tell the other therapists

anything like that. It was all in my head! The animosity isn’t real, the

conspiracy isn’t real, everyone against me isn’t real. It was all just a

feeling, me acting out a feeling. And for me that is the hardest thing

to take. Realizing that my feeling’s distort reality so much that I

can’t even tell what is real anymore, and then realizing that I have

been doing that my entire life. Repeating this vicious cycle over and

over and over. I think of how much time I’ve wasted chasing these false

ideas. All the untrue things my feelings led me to believe and how it

has made my life a complete mess.

But

I feel relieved as the session ends, like some weight has just been

lifted. And that is what makes this therapy so amazing. It is what makes

these therapists so amazing. They are able to pull these things out of

you, things you didn’t even know were there and not only recognize them

but feel them so you can change them and rebuild your life, a real life.

Case Study: Daryl—Three Non-Feeling Therapies

In cognitive behavioral therapy, the therapist focused almost exclusively on asking me to “change my negative thoughts” to more positive thoughts. For example, I was feeling very negative toward myself at the time this therapy occurred, and I would find this kind of self-talk happening within myself: “I’m a failure in my career.” The therapist would ask me to “re-word” this statement to myself to say, “I’m not succeeding in my career at the present time.” Well, this did not help at all. In fact, I simply got all jumbled in a lot of mechanistic ways of trying to handle internal problems that only ended in frustration and discouragement.

Another key approach of this cognitive behavioral therapist was to present me with a list of 12 “should” statements that people tend to use. Then, she would ask me to repeat the statement without using the word “should.” For example, one of the original statements might have been, “I should be more competent.” She would ask me to re-phrase this to say, “I am competent.” Of course, this did not help at all because I did not, in fact, become any more competent by simply saying, “I am competent. ” Much of her approach revolved around convincing me of the irrationality of my behavior in using “should” statements. To a great extent, she provided me with a list of rules and asked me to obey those rules. This approach completely ignored the feelings below the surface that were driving me to feel what I felt and, therefore, to say what I would say. Her approach did not take into account the principle of repression.

This therapist became very frustrated working with me. In fact, she discounted and denied the role of feelings in the therapeutic process. I reacted to her approach by being frustrated, discouraged, and disillusioned because her approach did not work for me.

In Jungian therapy, the therapist introduced me to the classical concepts within Jungian psychology: archetypes, anima, animus, collective unconscious, persona, shadow, active imagination, guided imagery, the Self, and interpretation of dreams. He also tried to stay within the classical Jungian psychological model in his therapeutic approach with me. He was a very intellectual person himself, and my gaining an understanding of these primary concepts was important to him. Therefore, he spent a lot of time with me in simply helping me to understand all of these Jungian terms and concepts. He did acknowledge and recognize the principle of repression, and he said that those things that have been repressed are now in “your shadow.” His whole approach resulted in one prerequisite to healing on the part of the patient: the patient must have an understanding of these terms, concepts, and principles. His premise was simple: once the patient gains an understanding of her/his problem and these Jungian concepts, healing will naturally occur. So, understanding automatically brings healing.

But, in my case, understanding did not bring healing. Understanding brought mental gymnastics. The process of gaining an intellectual understanding brought a false illusion of healing. I frequently said to myself, “Now that I have an intellectual (intelligent) understanding of what the problems are within me, I will be cured. I had this belief over and over, but it never did bring about true healing. Instead, it brought about a temporary false sense of confidence that “now I’ve got the problem nailed down, I will be okay.”

The Jungian approach helped only temporarily and then, only slightly. However, each time I came to understand the problem, I truly thought that I would be cured. It never happened. As a result I became discouraged and disillusioned. In fact, the process of intellectualizing actually slowed down the healing process in that it covered over the real feelings that needed to be felt.

In Gestalt therapy, the therapist gave an initial impression that feelings would play a primary role in my therapy. In fact, they never did. Gestalt therapy, for me, ended up somewhere in between cognitive behavioral and Jungian therapy. My Gestalt therapist made use of role playing as a way of trying to help me gain insights into my behavior. At times, she would say, “I want you to play your father and use this scenario.” At other times, she would ask me to play the role of the boss with whom I was having difficulty at that particular time. In all cases, the role-playing scenarios did nothing to bring about healing. The therapist was very impressed with her approach and what she thought was happening, but I was not experiencing anything significant in terms of real progress. Therefore, over a period of six months to a year, I became discouraged and disillusioned with the process. In fact, I lost confidence in this particular approach as well as in the therapist. She sensed my frustration and this caused friction in our relationship. Eventually, I discontinued my therapy with this therapist.

In conclusion, let me comment on what I see as the need for patients to evaluate and provide feedback to the therapist. It would be so simple for therapists of all psychological approaches to develop an evaluation/feedback form in order to seek feedback on how the therapeutic process is going. What the therapist thinks is occurring might not be the case at all.

Feeling better is fine. But

we must keep in mind that the caring we get now cannot make up for the

lack of it when it was critical. The critical period has passed. If it

hadn’t, then the doctor’s caring would heal us. Because it is after the

critical period, it is only palliative. It may help stabilize a shaky

defense system, but it never eradicates need. I will repeat ad nauseam:

we cannot love neurosis away. Even if we could resurrect Momma and have

her kiss and hug her grown-up child, no amount of love in the present

can reverse the damage. That is why a kindly therapist, who is concerned

and interested, cannot re-establish equilibrium in his patient. No

amount of his caring and insights will induce any profound change. No

psychotherapy can alter those needs, nor can the drug-taking or other

act-outs they drive, once they are sealed in.

More broadly, we must

keep in mind the futility of using ideas to treat the effects of deeply

ingrained traumas. As we shall see, it is not possible to use ideas and

thinking processes, which literally came along millions of years later

in the evolution of brain development, to affect what is lower in the

brain and evolved millions of years earlier. (page 52)

No amount of fulfilment later on can replace an early deficit of love and caring. This means that no amount of caring by a therapist can produce any profound change in the patient. She is long past her critical period. To repeat: you cannot love neurosis away. Of course, caring in the present can act as a holding action, keeping the real deprivation at bay for a short time; it tranquilizes but cannot be curative. And it has to be tranquilized all of the time lest the pain surge forth. That is why many patients seek conventional therapy ad infinitum. (page 109)

There is a book called The Blank Slate by Steven Pinker. (4) Dr. Pinker is a well-known writer on matters of the brain. His specialty is cognitive neuroscience. (“Cognitive neuroscience” seems to be one more oxymoron. If neuroscience limits itself to the study of the thinking brain, the rest of the central nervous system and its interrelationships with the thinking area are likely to be ignored.) Pinker claims throughout his work that nurture, the environment, is never a match for nature—what we inherit. He points out that criminals are rarely rehabilitated, which is proof, he believes, that criminal tendencies must be inherited. What he does not consider is first, the impact of early life shaping future criminals, and second, that perhaps our treatment of criminals is what is wrong, particularly when he is an advocate of the cognitive approach, which is bound to fail with criminals. The logic then continues: because we cannot make the criminal well, it must be because it is an inherited tendency. Naturally, this reasoning doesn’t put his therapeutic approach into question. Few, if any, professionals have seen the depths of the unconscious and observed the pain imprinted there. Therefore, they cannot know what nurture really is and what it can do to us. This is doubly true when the months of gestation and the first months of infancy are ignored. Because there is hardly any cognition going on, to speak of, in the first three years of life, when cognition is the focus, one is bound to ignore the most crucial formative times in life. (page 129/130)

I must hasten to add a caveat here. Nearly every cognitive/insight talk therapy fills the needs of the patient symbolically. The patient is acting neurotically in the hope of getting well. She is being a good, smart, helpful patient. The therapist is focusing only on her. How long has it been since someone paid exclusive attention to her? And for an hour! Is it any wonder that her therapy is addicting; the insights are a small adjunct to it all. The attention is preponderant. I point out elsewhere that the choice of the therapy is often another act-out. The patient is going back for love, caring, and approval. She gets it and it is another symbolic act, and therefore her neurosis is reinforced. The therapist gives us exactly what we needed from our parents; it is, unfortunately, 20 or 30 years too late. It is a bottomless pit that no one can fill. (page 135)

Constantly being on the move is a good example of this act-out; a mad flight from the feeling, just as others who feel as if they are failures are in a desperate search to try to feel like a winner. As I have noted, the definition of an act-out is behaving out of unfulfilled needs. Unfulfilled needs start the accelerator going. Even in depression, which looks like total lethargy and passivity, there is a highly active system. (page 137)

It is easy to become entangled in a mesh of thoughts that bind us, the more labyrinthine the better—hence the attraction of insight therapy. One is now a captive of those beliefs, and he enters into his slavery willingly, because this slavery is also an important defense. If fascism were ever to come to America, it would no doubt come by popular vote not by autocratic edict. We would slip into unquestioning obedience to the leader gladly, for it would relieve us of having to think for ourselves. He would protect us from the evil “out there.” I am reminded of those who dive for sharks in steel cages. They have no freedom of movement but it is a fact that the sharks cannot get to them. Their steel cage is their defense and their prison. Chemical prisons are just as strong as those steel ones. They allow for few alternatives in behavior. Beliefs are the psychic equivalent of repression. We can rechannel the flow but we will not change the volcanic activity. We can cap the explosion with ideas, but there is always a danger of another eruption; sometimes it is in the form of a seizure, other times it is found in being seized by a sudden realization—finding God and being born again. (page 178)

In rebirthing or LSD therapy, the patient is plunged into early remote pains; too often the result is incipient or transient psychosis. One of our patients went to a weekend meditation group that practiced deep breathing. (This was without our knowledge. It is forbidden in our therapy, for obvious reasons.) He came back to us in pieces, totally symbolic, speaking of cosmic forces and past lives. That deep breathing weakened his defenses and opened the gates artificially. The overload threw him into symbolism as the frontal cortex struggled to make sense out of liberated pains that were not ready to be felt and integrated. (page 183)

If we follow evolution and allow feeling before ideas in psychotherapy, then we cannot go wrong. If we defy evolution, and use ideas before feelings, then we must, perforce, go wrong. The same is true for those rebirthers who decide to plunge patients into remote and devastating pains right away in psychotherapy. There is no integration because the valence is so heavy and the pains are thrown up out of sequence. The same is true for those who use drugs and hallucinogens to get to deep early feelings. The system cannot possibly integrate (even though often the patient and therapist are convinced that progress has taken place). Integration means a slow descent from the present and top level prefrontal cortex to lower limbic/feeling areas and finally to the deeply rooted and engraved imprints around birth and infancy. We need to prepare the soil for heavy pains. When they intrude suddenly into the top level, there is of necessity a disintegration taking place. We see this in our vital sign research where signs go up and then down sporadically without any cohesion to them. They tell us there is no integration. (page 205)

A person is suspicious of being hurt by others because he was hurt so badly by insensitive parents; in Dan’s case, a cruel mother. He projected this fear onto others who he thought wanted to hurt him. Dan was slightly paranoid at the start of therapy, questioning even the nice things he would hear. “Did you really mean it? I thought you were putting me on.” His suspicions went from the personal and idiosyncratic (his mother in the past), to the general (everyone else in the present). “They” are trying to hurt me. When we took Dan back from the universal “they” and transformed it into a personal “me,” the paranoid ideas were diminished or eliminated. The general had become the particular, which then produced a general law. (page 211)

If the therapist has the need to be helpful and get “love” from the patient, he can act this out in therapy. I remember feeling my need to become a therapist and be helpful, trying symbolically to help my mentally ill mother to get well and be a real mother. No one is exempt from symbolic behavior. And it is certainly more comfortable for a patient to act out his needs and get them fulfilled (symbolically) in therapy, and imagine he is getting somewhere, than to feel the pain of lack of fulfillment. It is understandable that the idea of lying on a matted floor crying and screaming doesn’t appeal to some. Pain is not always an enticing prospect. Thus, the cognitive/insight therapist can be similarly deceived and entangled in the same delusion as his patient: both getting love for being smart. It is a mutually deceptive unconscious pact. (page 227)

Religion puts a moral slant on our hidden “evil” forces, but it amounts to the same thing. Psychology becomes religion by another name. If not, what are those impulses? Where do they come from? Are they immutable forces that cannot be changed? If not, how do we change them? Their leitmotif is that demons live inside of us that shall remain unalterable and nameless, a kind of genetic evil. We are born with it, and that is that. Here is where the cognitivists join the Freudians, who join the Jungians, who join the priests in thinking our main job is to hold down these dark, evil shadow forces. The reason that so many psychologists consider those negative forces immutable is that not having deep access, there is truly no way to change them, hence they are immutable. This is an example of circular logic. (page 228/229)

The following are two patients with two different kinds of compulsions. The first, a woman who must hang all her shirts in the same direction. She gets very nervous if one shirt isn’t hanging right. The insight in her feeling was, “I could never get it right. Nothing I could do would make my parents say, ‘You’ve done a good job.'” As it is with her shirts, she had to check over and over again because she still felt she didn’t get it right. She was acting out symbolically, “Everything I do is wrong. Nothing I can do will make them approve and love me.” Another patient is addicted to video games. It is not something he just plays; he is addicted and must do it. Why? To feel like a winner. No matter how many times he won, however, he still felt like a loser, something his father called him constantly. He was trying to shake that feeling, but never could. In life he felt like a failure; he didn’t know what else to do to get rid of that feeling. He chose, as in every neurosis, a symbolic channel. Until he felt in a session over and over again, “I’m not a failure, Daddy. Say I’m good— just once!” Feeling that stopped the act-out; he had to feel that many times. (page 252)

From Prisoners of Pain:

I use to believe in God but now I understand my religion was more or less an attempt to get closer to my dad, who was a devoted, if not dedicated Christian. That would have the way to close the gap between us, the way to look in his inner life and to show him mine. When I told him enthusiastically about my believe (enthusiasm based on hope I would finally get the answer I desired), no reaction came. It was like I casually had said something. Looking back I realized that from that moment I rejected the whole Christianity. What I intensely had hoped to get from my father, I hoped to get the same from God. I needed someone who could see my Pain, someone I could turn to and talk in confidence with. No one in my environment was like that, so God became that one. I couldn’t bear the Pain I was surrendered to, but that became the burden of an Almighty. All I needed was someone who could understand me; and if someone by definition could understand everything, the better it was. God was the father I wanted to have. God was the father in the sense of an enlightened authority, and Christ was the father of friendship and hope. Because I hadn’t succeeded to win my father for me by joining him in his ‘cage’, I stepped out determined and started to pound the bars. I wanted to challenge him to an open reaction from man to man. I got involved in the left-wing politics. It’s clear to me where I’m standing now that my involvement in this area (not to mention the objective correctness of my motive) was neurotically motivated. My passionate struggle against the establishment was a symbolic reflection of the struggle with my father. By attempting to make the establishment act justified by pointing on society’s injustice, I know that in reality I was trying to push him awake to tell him: ‘Look at me, dad; look what you’ve done to me!’ I remember saying very insulting things to him about politics, just to provoke him into a reaction. I did that because he usually was showing such a passive, non-reactive appearance. I symbolized my need for dad by demanding the rulers to take care of the poor and minorities. I proclaimed socialism because I wanted justice for all. (…) I never received what I needed. I stood up for the socially oppressed because for my own oppression

From The Primal Revolution: I believe that the war on drugs is part of the overall suppression that occurs in a neurotic society. The first reflex of unreal systems, both personal and social, against change is suppression. Drugs that aid suppression, which allow for accommodation to a suppressive mode of life, are considered ‘safe’. Drugs (like people) that tend towards liberation, towards feeling and towards acute insights, are the threat. There is much more evidence of the harm of cigarettes, evidence that indicates the ingestion of the nicotine drug over a period of time can be fatal. There is far less evidence that marijuana causes any harm. Why, then, do users of marijuana go to jail? Why is it all right for a person to get smashed on alcohol, endanger lives while drunk driving, and only have a driver’s license suspended, while a person in possession of LSD can go to prison, for decades in some cases. I don’t think that these are fortuitous events. They are the result of living in a suppressive society where feelings themselves become a threat. Indeed, feeling people would not accommodate to an unreal society, nor would they go out and kill their fellow men. Feeling people are indeed the threat to the business-as-usual group. (Page 112)

When I’m feeling shitty, I can either not like me and try to figure out what’s wrong with me, and all the shit I should go through to get me to like me, or I can just feel the pain. Many times I choose the mind trip, and cover up the pain. It hurts, dammit! I don’t want to feel it all the time. But always, sooner or later, the ‘thinking it out’ trip becomes ridiculous, and my Primals begin. (Page 136)

Give a depressive a new outlet, a new job, a party, or a chance to go shopping, and all of the inner-directed pressure now pours out in manic activity. He will literally ‘throw himself’ into his work. He will be ‘happy’ for those moments when his work will make him happy. What has really happenedis that he has found an outlet for tension – an outlet that continues to hide the Primal sadness. But great release of tension feels like happiness for the neurotic, and the relief feels better than that inner-pressured feeling that accompanies depression. So we can see that some of us shut down early in life and, sans outlets, become ‘dead’ and depressed. Others shut down and ‘act’ alive. If being the ‘happy clown’ pleases one’s parents, then the act will continue. The child will still be sad because he could not be himself. If there was no way to please, if one was disliked, suppressed, and rejected at every turn, then deadness and depression will result. Take away the ‘happy clown’s’ chances to perform, and the lurking sadness will begin to ascend. (Page 142)

Neurotic societies further the dichotomy between the mental and the physical. There are mental workers and physical ones (white-collar and blue-collar workers). In the popular mythology, labourers aren’t supposed to think or use big words, and intellectuals do not perform physical labour. Both, being split, may be exploited so that their brains and brawn are used and corrupted in the service of the system. The division between mental and physical workers means that an intellectual can study and work at something, coming up with solutions that have no relevance to real people. The worker can remain at a mindless job, never using his brain at all. In a real society there would be no dichotomy, no split between the body and mind worker. Intelligent people would not tolerate a neurotic, split society. They would not be content to work at unthinking jobs. I believe that the neurotic split has been the reason that a truly psychobiological psychotherapy has not been discovered heretofore. Mental workers (psychologists) have tried to find ‘mental’ solutions that were psychobiological. (Page 162)

From The Biology of Love:

Today’s conventional psychotherapist inadvertently and mistakenly reinforces the gating system of patients by using the tools of concern, listening, care, guidance, and advice. Therapy can become another act-out for the patient who is unconsciously getting what he wants (symbolic fulfillment) instead of what he needs (feeling the lack of fulfillment as a child). The implication is that you can have good intentions and love neurosis away. If all those fail, the therapist uses the more direct means of quelling need/pain by prescribing tranquilizers. A therapist who tries to build a patient’s self-esteem by telling her, “You really are capable, you know,” is actually encouraging the patient to block out her real feeling of “I’m bad. People don’t love me because I’m worthless.” By trying to “love” pain away by being “nice,” the therapist is fighting reality. He is functioning as the brain gate for the patient. In Primal Therapy, we want to open the gate and let in love, beauty, and life! To do that we must open the gate to real feelings of “No one loves me. I’m unlovable. It is all so hopeless,” etc. (Page 279)